1899-1994

Escaping Germany With her Husband to Black Mountain College

When the Nazis forced the Bauhaus School to close, flight was inevitable given Anni’s Jewish background. Emigration was facilitated by an almost casual invitation extended to them by Philip Johnson—he was visiting Berlin when he saw Anni’s unique wall hangings—to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Six weeks later a formal letter of invitation arrived, and on November 18, 1933, Anni Albers and her husband Josef (listed as “artist” to Anni’s “housewife”) sailed for the United States from Bremen, Germany.

Key Facts

As a student at the Bauhaus, Albers entered the weaving workshop because it was the only one open to her as a woman.

When they got to America, it was Anni who actually spoke on Josef’s behalf, because his English was minimal and she was quite fluent.

Albers elevated the status of weaving to an art form.

Albers played a key role in promoting the Bauhaus and its ideas in the United States.

Did you Know?

The Bauhaus style became highly influential in architecture and art, interior and graphic design, industrial design, and typography, as well as in arts education. Its style tended toward simple geometric shapes both rectilinear and curved, without elaborate decorations.

Early Years

Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann was born 1899 into an artistically—albeit commercially—inclined family in Berlin. Her mother’s family, the Ullsteins, were successful publishers and her father owned a furniture design and manufacturing company. Her family had nominally left Judaism. Anni was confirmed in the Lutheran church, but her sense of Jewish/Christian identity remained ambiguous. Her decision to study drawing and painting went against her family’s expectation to follow a traditional lifestyle. After studying for three years (1916–19) with the Prussian neo-impressionist Martin Brandenburg (1870–1919), she was accepted at the progressive Bauhaus in 1922.

Career Beginnings at the Bauhaus

The Bauhaus taught an aesthetic of radically simplified forms, rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass production could co-exist with the individual artistic spirit. In 1925, the year Anni and Josef Albers got married, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, where a shift took place from a focus on free play with forms to a more logical building of structures.

Anni developed functionally unique textiles combining properties of light reflection, sound absorption, durability, and minimized wrinkling and warping tendencies. Paul Klee greatly inspired her experiments with various series of boxes of graduating hues. These grid formations became essential to Albers’s wall hangings.

In 1930 Anni received her Bauhaus diploma and became acting head of the weaving workshop in 1931.

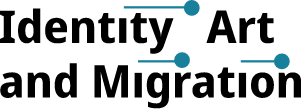

Anni Albers (at bottom right) and members of the weaving workshop, Bauhaus Dessau, c. 1927

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

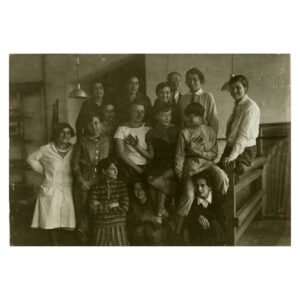

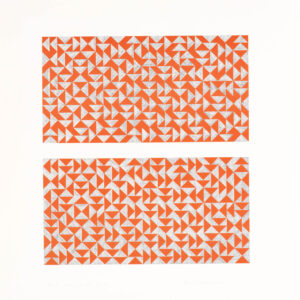

Preliminary Design for Wall Hanging, 1926

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY © 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Design for Jute Rug, 1927

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY © 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

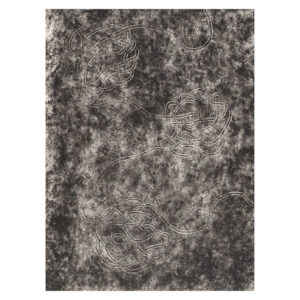

Line Involvement V, 1964

Two-color stone lithograph 19 ¾ x 14 ½ in. (50.2 x 36.8 cm). The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany 1994.11.5.e. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Coming to America

When the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close, the Jewish-born Anni and her already well-known husband, Joseph Albers, were able to immigrate to the United States. They were invited to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, a school that was just taking shape as a new experiment in college-level arts education with an emphasis on hands-on learning. Their weaving program was unique for its emphasis on the thread rather than purely coloristic or textural effects and for their limited range of hues.

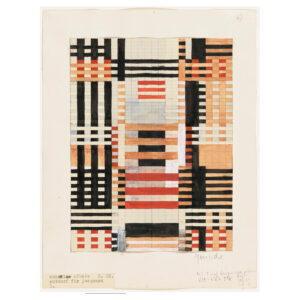

Anni Albers harvesting corn, Black Mountain College, 1935–36

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

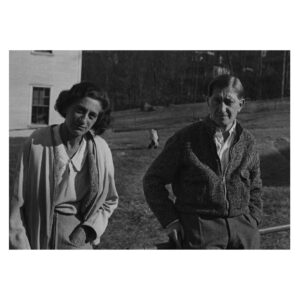

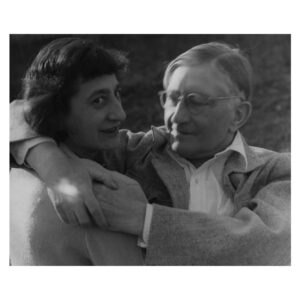

Anni and Josef Albers, Black Mountain College, 1938

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

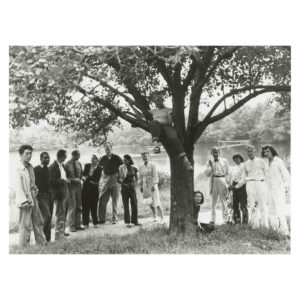

Summer Art Institute Faculty, 1946

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

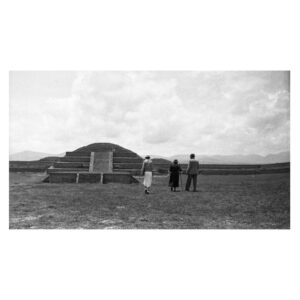

Josef and Anni Albers traveled extensively to Mexico to see the pre-Columbian sites and to South America, which reinforced the influence of Andean textiles on Anni’s work. In Veracruz, Mexico, Josef and Anni met up with Anni’s parents, who had come from Germany in June 1937 for a visit, and later permanently, fleeing Nazi persecution.

Anni Albers with her parents Toni and Siegfried Fleischmann, Teotihuacán, Mexico, 1937

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Monte Alban, 1936

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

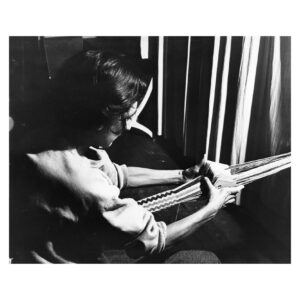

Anni Albers At Loom, Black Mountain College 1937

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the late 1940s, Albers began to make small-scale weavings that she called “pictorial weavings”. Her “pictures” remained entirely abstract, and she added a calligraphic element and more technical innovations, such as the supplementary knotted weft, a technique derived from a Peruvian source.

La Luz I, 1947

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Anni Albers winding a bobbin, Black Mountain College, 1941

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Anni Albers Card Loom/Card Weaving at Black Mountain College, n.d.

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Together with Black Mountain student, Alex Redd, she also began to produce innovative jewelry that utilized odd objects like hairpins, bottle caps, paperclips, glass drawer knobs, clay insulators, and kitchenware.

Anni Albers and Alexander Reed, Necklace, c. 1940

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Free-Hanging Room Divider, 1949

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY © 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

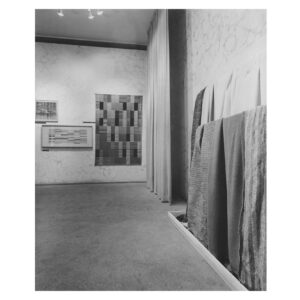

Installation view of Anni Albers Textiles, September 14, 1949–November 6, 1949

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Her weavings were widely exhibited in the 1940s, and she was in demand as a guest teacher and lecturer as well as, on occasion, a curator and as a writer.

The Decades after Black Mountain College

In fall 1949, Anni Albers became the first textile designer to have a solo exhibition at MoMA, Anni Albers Textiles. The show toured the US and Canada (to twenty-six museums) from 1950 to 1953. By that point, she was clearly established as one of the most significant designers of her era.

In 1950, Josef was appointed chairman of the Department of Design at Yale University and they moved to New Haven. Anni produced pictorial weavings working with Knoll, the manufacturer, on mass-producible patterns, while also teaching and lecturing throughout the country.

By 1963 she was shifting into printmaking. She quickly became enamored of the technique, so that thereafter she began to devote most of her time to lithography and screen printing. By 1970 Anni had given up weaving altogether in favor of printmaking.

Line Involvement V, 1964

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fox I, 1972

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Anni and Josef Albers, Black Mountain College, 1949

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Commissions of Jewish Context

The design for Torah Ark panels for Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, Texas, in 1957, was Anni’s first commission that explicitly involved a Jewish context. She received her second synagogue commission in 1961, for Torah Ark panels for Congregation B’nai Israel, in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. And in 1966 she was commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York to create a commemorative tapestry, Six Prayers. While Anni writes about the way she technically produced the result, no reference is made to what was being commemorated: the six million Jews who, trapped in Europe, perished during the Holocaust.

Study for Temple Emanu-El Ark Panels, 1957

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Interior of the Temple Emanu-El, Dallas, Texas, showing ark covering designed by Anni Albers, 1957

Six Prayers, 1966-67

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The following two decades were marked by diverse exhibitions and accolades. Anni’s honorary degrees and awards included a second American Craft Council Gold Medal for “uncompromising excellence” in 1981. At the presentation she was called a visionary, to which she responded that she preferred the term “experimenter.”

La Luz I, 1947

Linen and metallic thread; 18 ½ x 32 ½” (47 x 82.5 cm). The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany 1994.12.2. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

© 2021 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Promoting Weaving as an Artform

The United States presented Albers with new opportunities to develop as a designer of both functional and purely artistic textiles. She inspired a new generation of students through her teaching and produced an important body of writing on weaving that was informed by her extensive travels to Central and South America. Her efforts in all these areas elevated the status of weaving as an art form and her reputation as a major artist within that field. In addition to opening professional doors, Albers’ migration allowed her to play a key role in promoting the Bauhaus and its ideas in the United States through her participation in exhibitions and generous donations to American museum collections.

Watch the Conversations

From Sea to Shining Sea:

Anni Albers in America (1899–1994)

Featuring Laura Muir and Ori Z. Soltes, PhD

November 3, 2021

Additional Resources

Black Mountain College, VISIONARIES episode

Producer: Curator Helen Molesworth and Black Mountain College

Date: PBS premiere December 21, 2018

How to Weave Like Anni Albers | Tate

Producer: Tate. Filmed at Central Saint Martins, University of The Arts London in the Woven Textiles Workshop

Date: 2018