1915- 1994

“My father is a Jew, my mother is a Catholic, and I myself am nothing at all”

-Friedel Dzubas, letter to Prince Hubertus Löwenstein, February 4, 1941

Fleeing Germany as a “farmer”

Under Nazi law, Friedel Dzubas was considered Jewish because his father was Jewish, even though his mother was Catholic. In 1938 Dzubas was teaching art at a Jewish agricultural training camp and was thus eligible to list his profession as “farmer” when he applied for a visa to the US. The State Department prioritized agricultural immigrants but ultimately determined that Dzubas was not really a farmer. However, since he had been waiting for over a year, he received a non-preference quota visa in August 1939 and sailed from Liverpool on the Duchess of Richmond a few weeks later, on October 6th. After arriving in New York, he joined the staff at Hyde Farmlands, an estate in Burkeville, Virginia, set up to receive young German Jewish students who had trained in agriculture—in part so that they could receive preference on the quota waiting list.

Key Facts

Dzubas’ art often reflected the irreconcilable tension he felt between the Catholic and Jewish aspects of his identity.

He arrived in the United States when he was 25 years old, determined to become a successful artist in the New York art world.

He’s best-known for his large lyrical abstract works that were influenced by German and American Expressionists.

Did you Know?

In March 1938 the US quota for German born immigrants was 27,370. There were more than 300,000 people on the waiting list for US immigration visas by June 1939.

Early Years

Friedel Dzubas was born in Berlin in 1915 to a Catholic mother and Jewish father. Though his brothers underwent bar mitvah, Friedel at the age of 13 in 1934, did not. The Nuremberg laws of 1935 banning sexual relations and marriages between Aryans and Jews, affected his family.

Friedebald (Friedel) Dzubasz’s father and mother, Mannheim (Martin) Dzubasz (1875–1949) and Martha Medman-Schmidt Dzubasz (1880–1960), n.d.

Courtesy Silvia Dzubas and Jürgen Dzubas

Kulmbach, Germany, 1938

Courtesy Yad Vashem 13961. Chaim Drush 3015/1

By 1936, Dzubas knew that his only hope of becoming an artist lay in leaving Germany. Fortunately he was hired to lead art classes while also training as a farmer at a Jewish agricultural training camp near Gross-Breesen, preparing Jewish teenagers to move to North and South America.

On the night of the November Pogrom on November 9th and 10th, 1938 (Kristallnacht), Friedel’s brother Kurt’s newspaper and candy kiosk was among the thousands of buildings and businesses burned and Kurt was sent to a labor camp. The Gestapo then placed all the trainees at Gross-Breesen under house arrest, and had Friedel not been away in Berlin that day he would have gone to Buchenwald concentration camp.

Kulmbach, Germany, 1938

S.S. men leading a woman through the streets wearing a sign that reads: “I am a swine. I slept with a Jew, Karl Strauss, and thus polluted the German race.”

Courtesy Yad Vashem 13961. Chaim Drush 3015/1

Having secured his visa, Dzubas left his family behind and fled Germany in October 1939. He went to work at Hyde Farmlands in Virginia, which was set up to receive the young Jewish farmers from Gross-Breesen. Hyde Farmlands never turned a profit and closed in 1941, but at least thirty Jewish teenagers were able to escape Germany as “farmers.”

Career Beginnings

Dzubas settled in New York, where he eventually established himself as an independent book designer, primarily of non-fiction, for the Philosophical Library, while continuing to paint. He rented a summer home in Woodstock in 1948. When he learned that the artworld’s most powerful critic, Clement Greenberg, was looking to share a house in the country he introduced himself and offered his place. Greenberg and Dzubas had a close relationship that lasted until they both died in 1994.

By the end of the 1940s and early 1950s he was part of the center of the art world defined by American Abstract Expressionism in New York. In addition to his friendship with Greenberg he shared a studio with Helen Frankenthaler in the early 1950s, and his work was included in group exhibits at the renowned Leo Castelli Gallery.

Dzubas’s paintings are as dependent upon bold relationships of disembodied, radiant color as those of his American-born colleagues Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, or Morris Louis. But Dzubas’s paintings are also notable for a European intensity and resonance.

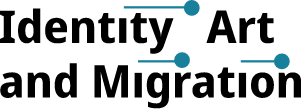

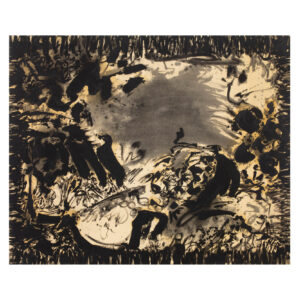

Early Grave, 1957

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Virgin, 1962

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Religious Themes

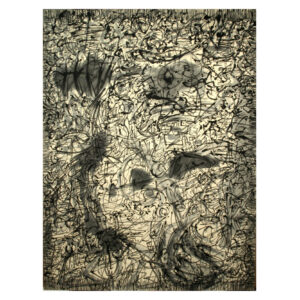

Dzubas’ shifting sense of self as Jewish or Catholic resonates through particular paintings and drawings done over the years. In Early Grave, from 1957 for example, the Catholic iconography of the cross is highly abstracted but visible. Dzubas constructed allegories, as in the “black drawings,” and in later abstractions such as Early Grave, Virgin, and Patmos.

Patmos, 1974-75

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Returning to Germany for Ten Months

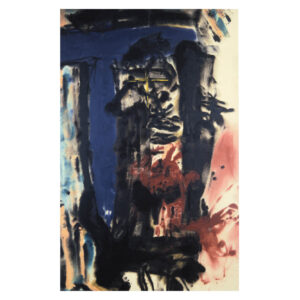

In 1959 Dzubas went back to Germany to visit his family after 20 years in the US. After this visit, he began to paint the “black drawings” where his conflicted feelings about his Jewish identity become more evident. He said “In those ten months in southern Germany and Austria . . . I rediscovered certain attitudes that come out of Catholicism as being quite potent.”

Monk, 1960

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Betrayal, 1960

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Temptation, 1960

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For some of the later “black drawings” Dzubas chose the round tondo format, a shape that often occupies the highest and most imposing space in medieval churches, like the rose window with its dense tracery around interlocking pieces of stained glass.

Blackbird, 1960

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rex, 1961

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

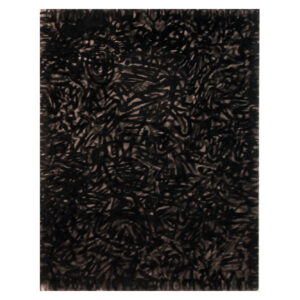

He also included a self-portrait in this series. Here, black-ink-like splotches …form a negative contour, a “frame,” that presumably hints at a facial structure.

He later recalled, “[…] when I did those all-over black, dense compositions, it was already at all unessentials […]. Naturally, color came more and more into play, and I discovered that what I can reach emotionally and express by color is infinite. It’s composed of two seemingly unrelated sources – there’s a Nordic, northern European kind of grayness that I am closely related to, but there’s also great affinity for Mediterranean Matisse, so to speak. It’s almost as that’s the humane side of me, and the gray business is the barbaric one. But I have them both.”

Self-Portrait, 1961

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Red Heart, 1980

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cleavage, 1990

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

An American Modernist

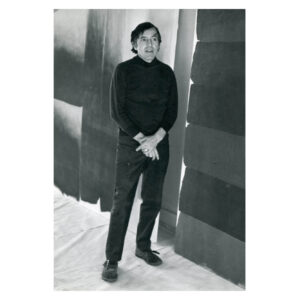

Dzubas went on to have a well-regarded career—both as a teacher at noteworthy colleges and universities throughout the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s; and as a painter of usually very large and lyrical abstract works that were shown in more than sixty solo exhibitions around the world. He died in Newton, MA in 1994.

Friedel Dzubas with Helen and M. Hughton in 1977 at Andre Emmerich HF Opening

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Friedel Dzubas in his studio in Ithaca, NY, c. 1974 with Trough, 1972 (l.) and Found, 1972 (r.)

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Red Heart, 1980

Magna on canvas, 72 x 72 in. (182.8 x 182.8 cm). Private collection

© 2021 Estate of Friedel Dzubas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Duality… Painter of Large Lyrical Abstract Works

By the 1970s Dzubas had created a striking visual language in his paintings, with counterpoised abstract shapes of brushed color that he juxtaposed, overlapped, and opened to reveal his gessoed grounds. His early work was influenced by Expressionist artists of the two primary groups known as Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter. As Dzubas told curator Charles Millard in 1982, “Their unheard-of brashness of color; that was really brave. That was very exciting. Color’s an emotional thing. These people not only spoke directly; they felt deeply. There was passion.” He continued to explore his emotions and identity through the expressive use of color, or lack of it, throughout his career.

Watch the Conversations

Remembering Friedel: An Intimate View of Friedel Dzubas (1915-1994)

Featuring Karen Wilkin and Sandi Slone

October 27, 2021

Additional Resources

Installation of Friedel Dzubas’ painting “Crossing” (1975)

Director: Bill Fertik

Producer: Tower 49 Gallery

Date: 2016